Translate this page into:

Comparative Study of Glasgow Coma Score, Poisoning Severity Score and APACHE 2 Score in Predicting Outcome of the Patients with Organophosphate Poisoning

*Corresponding author: Archana Deshpande, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Government Medical College, Nagpur, Maharashtra, India. arcsandeshpande@rediffmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Rathod N, Deshpande A. Comparative study of Glasgow coma score, poisoning severity score and APACHE 2 score in predicting outcome of the patients with organophosphate poisoning. Vidarbha J Intern Med 2022;32:29-34.

Abstract

Objectives:

This study aims to calculate and compare Glasgow Coma Score, International Program on Chemical Safety Poisoning Severity Score and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation 2 score in predicting outcome of the patients with organophosphate compound poisoning.

Material and Methods:

A total of 100 patients were taken in the study from December 2018 to December 2020. Glasgow Coma Score (GCS), International Program on Chemical Safety Poisoning Severity Score (IPCS PSS) and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation 2 (APACHE 2) score of each patient were calculated and compared. In this study, we compared the GCS, IPCS PSS and APACHE 2 score in predicting the outcome of the patients with organophosphate compound poisoning.

Results:

Of the 100 patients, 70 were male and 30 were female. Mortality was 15% in the study. APACHE 2 score was found to be more accurate than IPCS PSS and GCS in predicting the outcome of the patients with OP poisoning.

Conclusion:

APACHE 2 score requires arterial blood gas analysis which might not be available at all primary health care centres. At such places, IPCS PSS is the better option for predicting the outcome of OP patients.

Keywords

Organophosphate compound

Glasgow Coma Score

International Program on Chemical Safety Poisoning Severity Score

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation 2 score

INTRODUCTION

India is a predominantly agrarian country where pesticides are routinely used for farming. According to data available from National Poison Information Centre India, suicidal poisoning with household agents (organophosphorus [Ops]) is the most common modality of poisoning.[1] Worldwide, an estimated 3,000,000 people are exposed to organophosphate agents each year, with up to 300,000 fatalities.[2] OP compounds have been widely used for quite a few decades in agriculture for crop protection and pest control, thousands of these compounds have been screened and over 100 of them have been marketed for these purposes.[3] They bind to acetylcholinesterase (AChE), also known as red blood cell AChE, and render this enzyme non-functional. AChE is the enzyme responsible for hydrolysis of acetylcholine to choline and acetic acid, and inhibition leads to an overabundance of acetylcholine at the neuronal synapses and the neuromuscular junction.[4,5] The diagnosis of OP poisoning is based on clinical features as observed by the treating physicians. Organophosphate poisoning is a serious condition that needs rapid diagnosis and intensive care support. In a country like India with limited resources, it is vital for us to know which patients might require tertiary care management, hence, we need proper indicators to help us judge the severity of the poisoning so that the patients can be triaged and then sent to tertiary care hospital from the rural health care centres. In this study, we compared the Glasgow Coma Score (GCS), International Program on Chemical Safety Poisoning Severity Score, (IPCS PSS) and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation 2 (APACHE 2) score for predicting the outcome of organophosphate poisoning patients so that the serious patients can be transferred to tertiary care centre at the earliest.

Aims and objectives

This study aims to calculate and compare the accuracy of GCS, IPCS PSS and APACHE 2 in predicting the outcome of the patients with organophosphate poisoning.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

A prospective observational study was carried out at Government Medical College and Hospital, Nagpur, from December 2018 to December 2020. A total of 100 patients were included in our study that was satisfying the inclusion criteria after obtaining proper consent from the patient or legally authorised relative. The study was approved by the ethical committee of the hospital.

Inclusion criteria

Consecutive cases of organophosphate poisoning admitted in the intensive care unit (ICU) of our hospital were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with mixed poisoning, chronic health conditions such as chronic liver disease and chronic kidney disease or patients on steroids were excluded from the study.

Sample size calculation

Based on the previous studies, the following assumptions were made.

-Area under curve for PSS is 0.78

-Absolute precision is 8%

-Derived confidence level is 95%

Statistical analysis

Collected data were entered into the Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Tables and charts were prepared with the help of Microsoft Windows 10 Word and Excel.

Study protocol

Diagnosis was done on the basis of history of intake and clinical examination characteristic of OP poisoning such as hypersalivation, miosis, fasciculations, odour of OP compound and serum cholinesterase levels. All cases were treated with repeated doses of intravenous atropine and oximes as per standard protocols. GCS, IPCS PSS and APACHE 2 score were applied to all the patients.

RESULTS

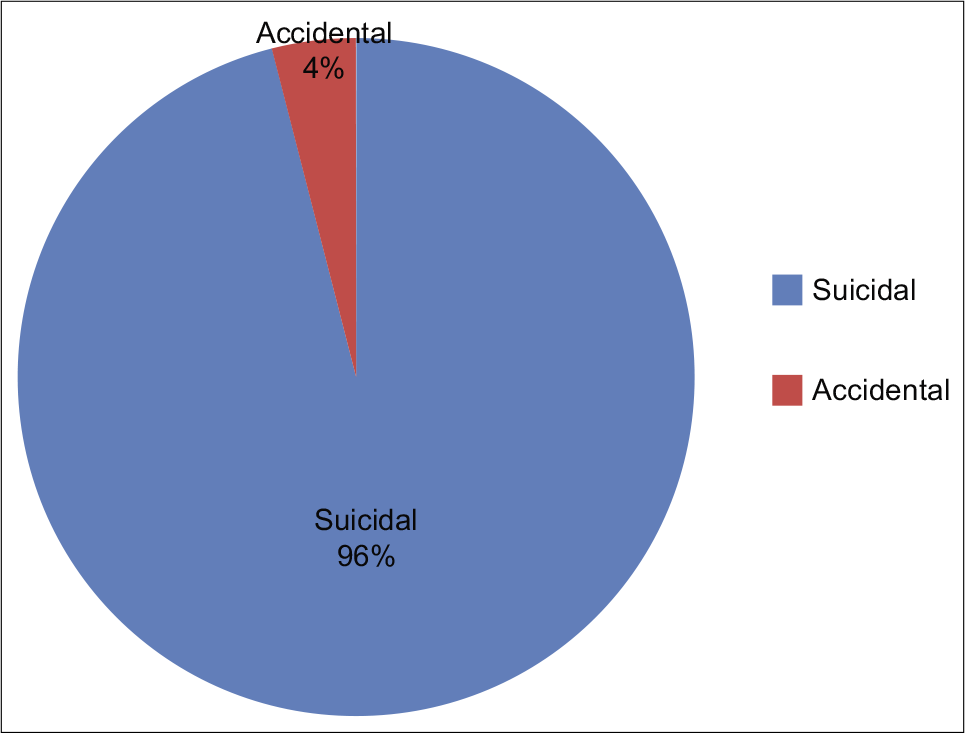

About 96% of the cases were suicidal and the rest 4% were accidental consumption.

The pulse rate, SpO2, blood urea, serum creatinine, PaO2 and PaCO2 showed statistical significance with the outcome of the patients.

About 34% of the patients who required ventilator support succumbed.

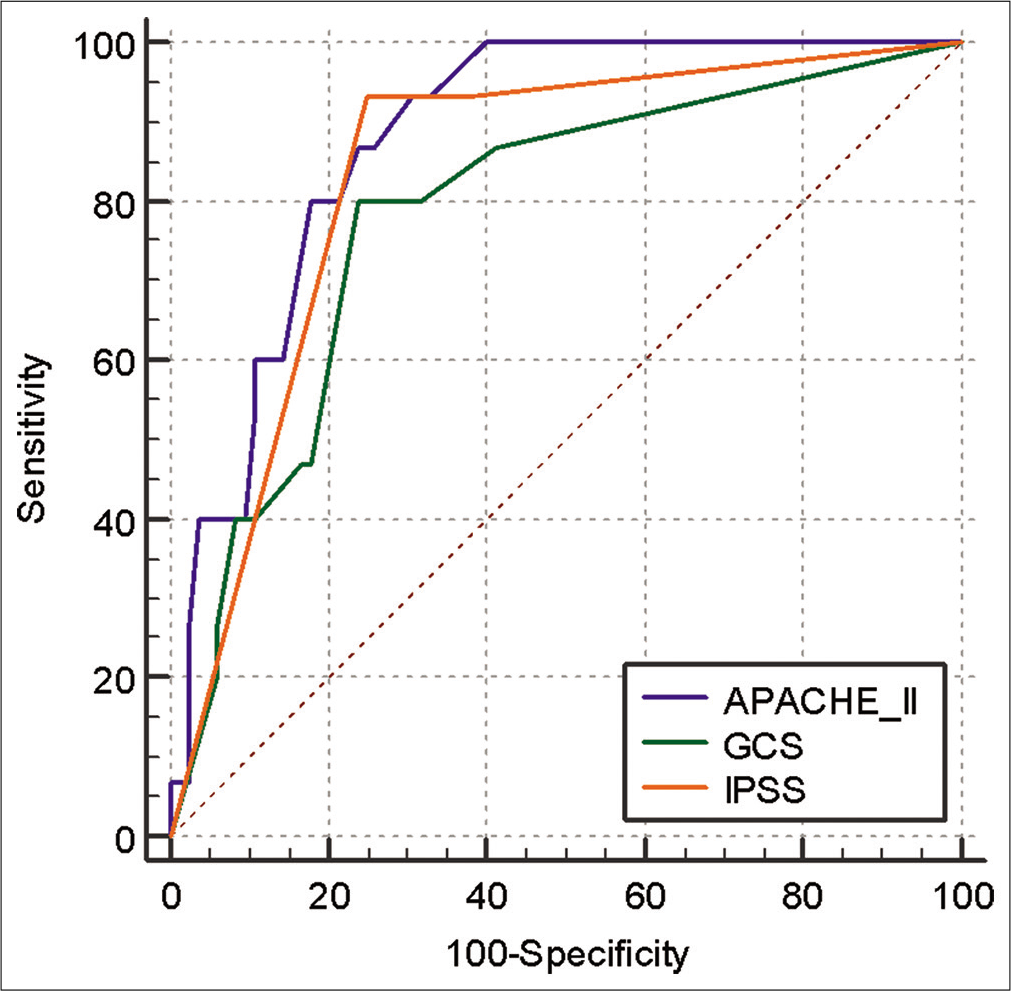

From the above [Tables 1-9], it was seen that APACHE 2 (AUC – 0.881) was a better predictor of mortality followed by IPCS PSS (AUC – 0.839) and GCS (AUC – 0.785) [Figures 1-3].

| Age in years | Number of cases | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11–20 | 18 | 18.0 | |

| 21–30 | 33 | 33.0 | |

| 31–40 | 22 | 22.0 | |

| 41–50 | 11 | 11.0 | |

| 51–60 | 10 | 10.0 | |

| >60 | 6 | 6.0 | |

| Total patients | 100 | 100 | |

| Mean age | 34.25±14.80 (14–83) | ||

| Parameters | Non-survivors | Survivors | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age | 37.06 | 17.44 | 33.75 | 30.65 | 0.4269, NS |

| Pulse rate | 117.4 | 23.64 | 97.04 | 19.77 | 0.0006, HS |

| Temperature | 97.66 | 0.48 | 97.58 | 1.98 | 0.8801, NS |

| SBP | 119.33 | 22.50 | 115.41 | 15.00 | 0.3921, NS |

| DBP | 77.33 | 12.22 | 75.88 | 7.76 | 0.5456, NS |

| Respiratory rate | 14.33 | 4.83 | 15.72 | 2.00 | 0.0584, NS |

| SpO2 | 93.67 | 5.86 | 97.01 | 2.46 | 0.0003, HS |

| Hb | 11.76 | 3.13 | 11.92 | 1.90 | 0.7957, NS |

| WBC | 13.14 | 7.27 | 11.70 | 5.32 | 0.3631, NS |

| Platelet count | 235.06 | 131.03 | 216.57 | 85.82 | 0.8810, NS |

| Haematocrit | 35.6 | 8.56 | 36.90 | 6.81 | 0.5136, NS |

| Blood urea | 31.13 | 17.63 | 24.15 | 10.94 | 0.0425, S |

| Serum creatinine | 1.07 | 0.42 | 0.84 | 0.26 | 0.0056, HS |

| Serum cholinesterase | 1462.72 | 2274.23 | 1937.20 | 20.26.98 | 0.0718, NS |

| PaO2 | 81.88 | 27.82 | 92.23 | 26.78 | 0.0659, HS |

| PaCO2 | 45.19 | 10.02 | 40.11 | 4.56 | 0.0019, HS |

| MAP | 90.8 | 15.02 | 88.83 | 9.45 | 0.5030, NS |

| pH | 7.29 | 0.16 | 7.39 | 0.08 | 0.006, NS |

OP: Organophosphorus

| Gender | Number of cases | Non-survivors | Survivors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 70 | 10 | 60 |

| Female | 30 | 5 | 25 |

| Total patients | 100 | 15 | 85 |

| GCS | Number of cases | Non-survivors | Survivors | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14–15 Mild | 61 | 3 (4.92) | 58 (95.08) | |

| 9–13 Moderate | 18 | 5 (27.78) | 13 (72.22) | Chi-square=12.70 |

| 3–8 Severe | 21 | 7 (33.33) | 14 (66.67) | P=0.002, HS |

| Total | 100 | 15 | 85 | |

| Mean GCS | 8.53±4.15 | 12.81±3.56 | <0.0001, HS |

GCS: Glasgow Coma Score

| IPCS PSS score | Number of cases | Non-survivors | Survivors | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade-1 | 54 | 1 (1.85) | 53 (98.15) | |

| Grade-2 | 11 | 0 | 11 (100) | Chi-square=26.42 |

| Grade-3 | 35 | 14 (40) | 21 (60) | P<0.001, HS |

| Total | 100 | 15 | 85 | |

| Mean PSS | 2.86±0.51 | 1.62±0.86 | <0.0001, HS |

IPCS PSS: International Program on Chemical Safety Poisoning Severity Score

| APACHE score | Number of cases | Non-survivors | Survivors | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–5 | 58 | 1 (1.72) | 57 | |

| 6–10 | 13 | 2 (15.38) | 11 | Chi-square=25.94 |

| 11–15 | 15 | 6 (40) | 9 | P<0.001, HS |

| 16–20 | 9 | 3 (33.33) | 6 | |

| 21–25 | 3 | 2 (66.67) | 1 | |

| ≥66 | 2 | 1 (50) | 1 | |

| Mean | 15.46±6.50 | 5.42±6.07 | <0.0001, HS |

APACHE: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

| Hospital stay | Number of cases | Non-survivors | Survivors | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–4 | 8 | 8 (100) | 0 | |

| 5–9 | 63 | 5 (7.94) | 58 (92.06) | Chi-square=49.5744 |

| 10–14 | 23 | 2 (8.70) | 21 (91.30) | P<0.001, HS |

| >14 | 6 | 0 | 6 (100) | |

| Mean | 9.67±4.81 | 4.87±3.47 | 0.0004, HS |

| Number of patients | Non-survivors | Survivors | |

|---|---|---|---|

| On ventilatory support | 44 | 15 | 29 |

| Not on ventilatory support | 56 | 0 | 56 |

| Parameter | Area under curve | Standard error | 95% confidence interval | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCS | 0.785 | 0.063 | 0.691–0.861 | FAIR |

| IPCS PSS | 0.839 | 0.044 | 0.752–0.905 | GOOD |

| APACHE 2 | 0.881 | 0.036 | 0.801–0.937 | GOOD |

GCS: Glasgow Coma Score, IPCS PSS: International Program on Chemical Safety Poisoning Severity Score, APACHE: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

- Gender Distribution in the Study Subjects

- Pie chart showing the reason for consumption.

- The Sensitivity and specificity of APACHE 2, GCS and IPSS

DISCUSSION

Of the 100 patients included in the study, 70% were male and 30% were female. This finding correlated well with the studies done by Mundhe et al.[6] and Rajeev and Arvind,[7] where there was a male predominance too (62.85% and 66%, respectively). Males have more access to OP compounds than their counterparts. Furthermore, occupational exposure tends to be more in males. Total mortality in the study was 15%. The mean age in the present study was 34.25 ± 14.80. Majority of the patients belonged to the age group of 21– 30 years (33%) followed by 31–40 years (22%). The studies by Mundhe et al.[6] and Rajeev and Arvind[7] reflected the same. This age group is the most productive age group of the society prone to accidental exposures. In today’s hectic, stressful and competitive world, the major burnt is usually on this age group probably leading to them undertaking extreme steps such as attempting suicide. Maximum number of patients had a GCS of 14–15 (61%) followed by 3–8 (21%) which was followed by 9–13 (18%). Maximum number of deaths were seen in patients who had GCS of 3–8 (33.33%) followed by 9–13 (27.78%) and finally 14–15 (4.92%). This correlates well with the study of Davies et al.,[8] patients who present with a GCS n13 need to be treated aggressively and monitored very closely. The mean GCS was 8.53 ± 4.15 in the patients who died and it was 12.81 ± 3.56 in the patients who survived. This correlation was statistically significant. The study done by Muley et al.[9] who also pointed out that the mean GCS was lower in the ventilated group of patients. Maximum number of cases were in Grade-1 which was 54 (54%) which reported 1 (1.85%) death. Grade-2 had 11 (11%) cases and 0 (0%) deaths. Grade-3 reported 35 (35%) cases and had 14 (40%) deaths. Mean IPCS PSS of the cases who died was 2.86 ± 0.51 while it was 1.62 ± 0.86 in the patients who were discharged. These findings correlate well with the study done by Davies et al.[8] Patients with higher grade of IPCS PSS on admission had more mortality than those with lower grade of IPCS PSS. Maximum number of patients had 0–5 (58%) scores of which 1 (1.72%) died. Maximum number of deaths 1 (50%) were seen in cases who had a score of admission had more mortality than those with lower grade of IPC± 6.50 and for the patients who were discharged, it was 5.42 ± 6.07. These findings correlate well with the study done at Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Sciences by Sam et al.[10] The present study revealed that APACHE 2 score (AUC = 0.881) was significantly better in predicting mortality in OP patients as compared to GCS (AUC = 0.785) with P = 0.0212 but it was not significantly different from IPCS PSS (AUC = 0.839) with P = 0.1971. There was no significant difference between IPCS PSS (AUC = 0.839) and GCS (AUC = 0.785) with P = 0.2492. Hence, APACHE 2 score is better followed by IPCS PSS which is followed by GCS in predicting the outcome of OP patients. This correlates well with the study done by Sam et al.[10]

CONCLUSION

Applying different scoring systems at first medical attention often help to recognise the severity and later help for early referral to a tertiary care hospital for ICU support. APACHE 2 was found to be more accurate than IPCS PSS followed by GCS in predicting the outcome of the patients with OP poisoning.

Implications

Education of the masses against the deleterious effects of OP compound consumption is essential. Steps should be taken for minimisation of OP compound exposure as an occupational health hazard. All medical personnel at all hospitals should be trained regarding OP poisoning management. The importance of early initiation of treatment thus reducing the lag time should be stressed. The government needs to impose strict laws on the sale of dangerous OP compounds and alternate insecticides which are less lethal to humans should be made widely available for the public. APACHE 2 score requires ABG which is usually not available at rural health centre. At such centres, IPCS PSS can be used to triage the patients who require urgent intensive care. GCS, IPCS PSS and APACHE 2 score are important bedside tools for assessing the need for ventilatory support and the outcome. These scales can be used to triage patients for intensive monitoring and timely institution of critical care support.

Risk factors

None.

Declaration of patient consent

Consent of Patient/Legally authorised Representative have been taken.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- An epidemiological study of poisoning cases reported to the national poisons information Centre, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2005;24:279-85.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The role of oximes in the management of organophosphorus pesticide poisoning. Toxicol Rev. 2003;22:165-90.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxidative and biochemical alterations induced by profenofos insecticide in rats. Nature Sci. 2009;7:1-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hazards of chemical weapons release during war: New perspectives. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107:985-90.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The clinico-demographic study of morbidity and mortality in patients with organophosphate compound poisoning at tertiary care hospital in Rural India. Int J Adv Med. 2017;4:809-18.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Study of clinical and biochemical parameters in predicting the need for ventilator support in organophosphorus compound poisoning. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2013;2:9555-71.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Predicting outcome in acute organophosphorus poisoning with a poison severity score or the Glasgow coma scale. QJM. 2008;101:371-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To identify morbidity and mortality predictors in acute organophosphate poisoning. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2014;18:297.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poisoning severity score, APACHE 2 and GCS: Effective clinical indices for estimating severity and predicting outcome of acute organophosphorus and carbamate poisoning. J Forensic Leg Med. 2009;16:239-47.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]